By Catherine Zuckerman. National Geographic.

In one giant sequoia’s lifetime multiple generations of humans will be born and die. These enormous trees, native to California, can live for thousands of years. Though that time frame is considerable, writes photographer Beth Moon in her book, Ancient Skies, Ancient Trees, “compared to the age of the stars above, it is not even a blink of an eye.”

A self-taught photographer with a fine art background, Moon has been photographing trees for 20 years. She spent much of that time shooting on film and then processing her images using a 19th-century black-and-white method called platinum palladium printing. For more than a decade she photographed trees all over the world from sunrise to sunset.

But then Moon came across a scientific study that suggests a correlationbetween tree growth and galactic cosmic radiation. “As I thought about it,” she says, “it made so much sense; you know the sun is a star anyway—so why wouldn’t there be this very strong correlation with starlight at night as well as our sun during the day?”

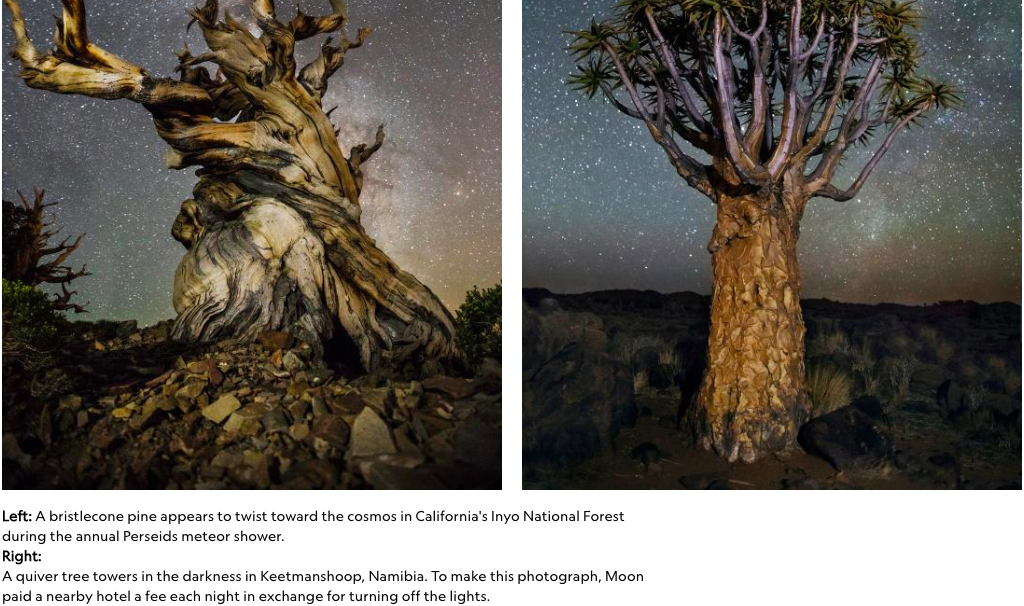

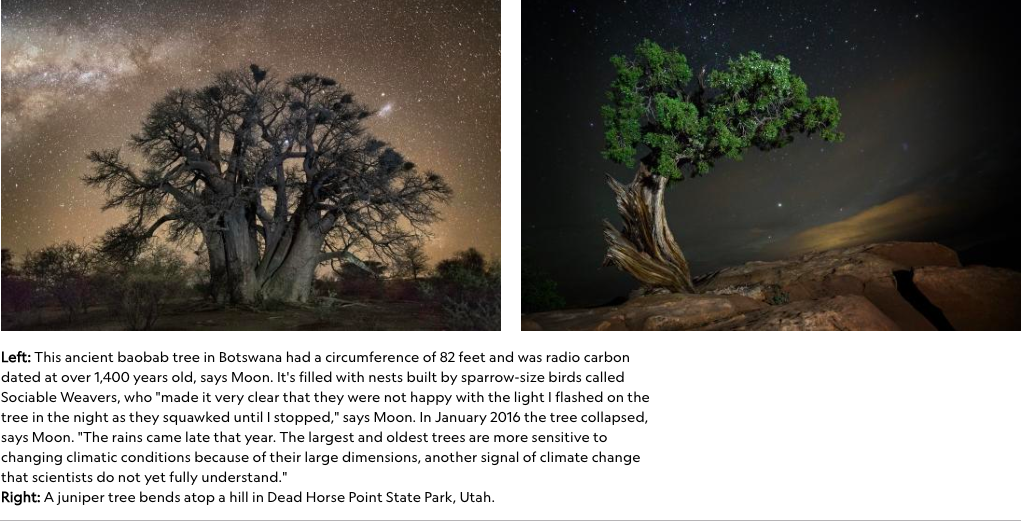

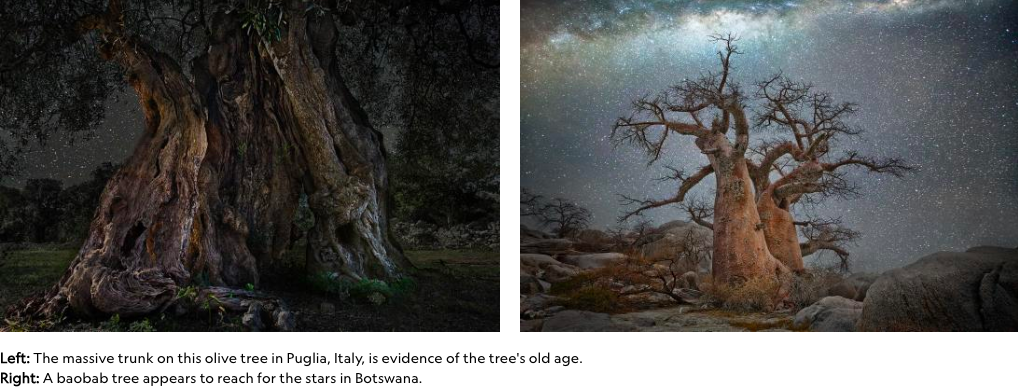

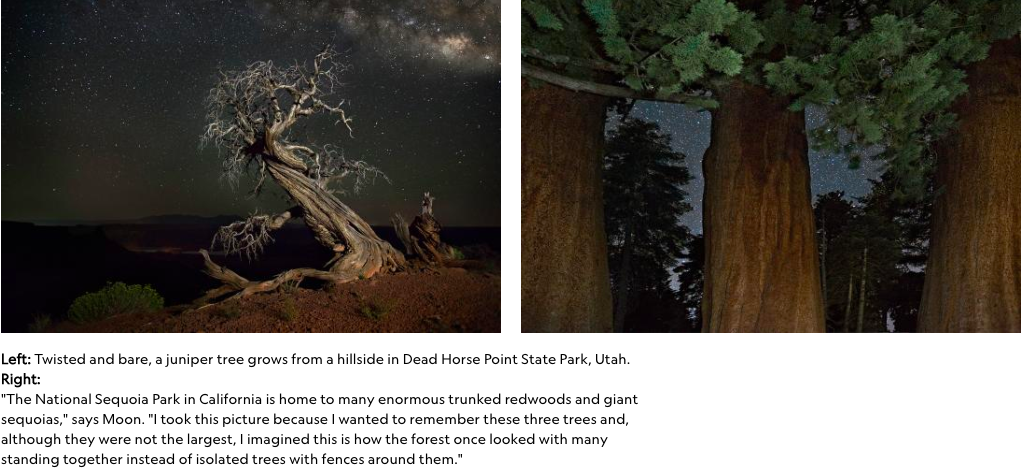

The idea for her project, Diamond Nights, was born. Over the next three and a half years Moon traveled around the United States and also to several other countries, including England, Italy, Namibia, and Botswana, documenting ancient baobabs, junipers, sequoias, and more under skies blanketed in stars. Her mission was simple: Find out where the world’s darkest places overlap with the world’s oldest trees, go there, and make beautiful photographs. (Learn why light pollution harms Earth.)

Execution of this plan, of course, was not quite as simple.

First of all, Moon says, lots of places have either old trees or dark skies, but not both. When the two do intersect, the location is often challenging to reach. So Moon hired local guides to help her seek out her woody subjects, which were sometimes in extremely remote areas. “We would travel all day long never seeing another person, a sign, or even any roads,” she says. On these occasions Moon would camp under the tree, eating canned sardines for sustenance and patiently waiting for clouds to drift in and out of her frame.

For Diamond Nights, Moon made the transition from film photography to digital capture. It’s a more light-sensitive technique, she says, and results in incredibly vivid images. Planning all her shoots around moonless nights, she wanted each tree to be primarily bathed in starlight, with additional glow from flashlights, for example, as necessary. (Find out how trees secretly talk to each other in the forest.)

Because of the dark conditions, Moon set her camera on a slow shutter speed. This meant standing by for wind, and pausing during gusts. “With a 30-second exposure you don’t want the branches shaking,” she says. “So there was a lot of downtime.”

Though Moon is not a scientist, she has become interested in the scientific aspect of trees as well as light pollution. Some of the “wildest” places she sought out, she says, were actually spoiled by artificial light coming from nearby buildings and towns. “It has been said that mankind’s destiny is written in the stars,” she writes in her book, “but it will be a very bleak destiny” if we eventually can no longer see them.